REPOSTED FROM Ann’s blog at www.yourcoachingbrain.wordpress.com

“This bed is too hard, and that bed is too soft, but the little bed is JUST RIGHT,” said Goldilocks, as she lay down and fell asleep. But then the bears came in….

“This bed is too hard, and that bed is too soft, but the little bed is JUST RIGHT,” said Goldilocks, as she lay down and fell asleep. But then the bears came in….

A Quick Intro to the Pre-Frontal Cortex – and how this relates to coaching

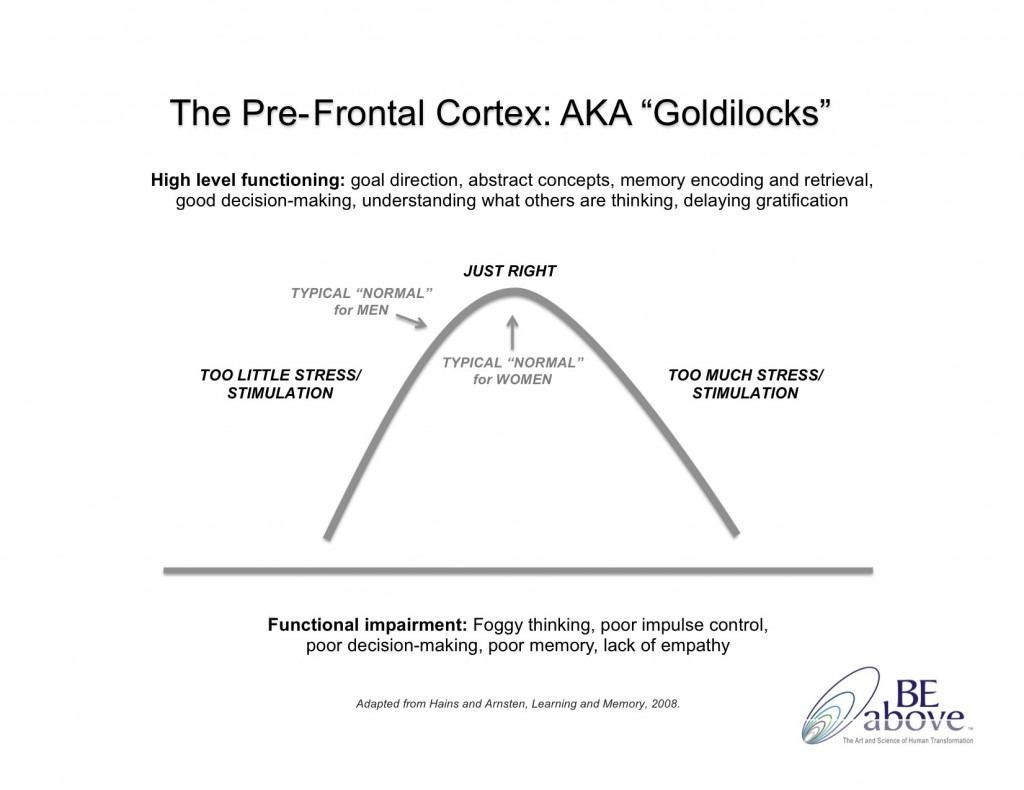

First of all — what is the pre-frontal cortex (PFC), anyway? Well, this part of our brain plays a role in many important “executive functions,” or high-level thinking such as:

- Pursuing goals and thoughtfully guiding our actions;

- Dealing with things that are conceptual rather than concrete;

- Encoding important memories and retrieving appropriate memories so they can be used to inform current decisions;

- Helping us to make thoughtful decisions, use our insight, demonstrate good judgment, and be flexible;

- Understanding what what others are thinking;

- Monitoring errors;

- Understanding what is real vs. what is imagined or remembered; and

- Allowing us to delay gratification[1]

When I heard Yale professor Amy Arnsten liken the PFC to the character Goldilocks, in that it needs to have everything just right in its chemical environment in order to function optimally, I knew I would never forget it. (Metaphor is such a great teaching tool. I’ll have to devote a blog post just to that sometime, but for now, let me just say that it really does help us remember things.)

Here’s how it works technically: being tired, bored or unmotivated releases very small amounts of catecholamines (hormones produced by the adrenal glands) such as dopamine and norepinephrine, while being stressed creates a massive and constant flow. The ideal state is that of being alert and interested, in which case short bursts of catecholamines are released in response to stimulus in the environment.

In both the case of too little catecholamine activity and too much, the effect on the PFC is to put it in a state of distraction, disorganization, forgetfulness, and lack of inhibition, while the perfect amount of catecholamine release enables the person to be focused, organized and responsible. In other words (I find this fascinating) too little engagement and too much stress both take us to the same ineffective place. In order to be at our best, we need to be in balance.

As coaches, we often see both sides of this continuum. I myself have worked with many leaders who have become disengaged(often due to working for other leaders who are themselves overloaded on catecholamines due to stress and are thus leading in a reactive way) and are hanging on in an organization fueled only by either loyalty to the mission or fear of not having another job. One brilliant, dedicated leader I have been coaching told me that she simply gave up at one point when her boss made one more uninformed decision and overrode her authority. She stopped caring and said she knew she had lost her edge and literally felt stupid. She felt she wasn’t making decisions well and was wondering what value she brought to the organization. Quite possibly a case of too few catecholamines.

On the other end of things I have no end of stories of leaders who have become swept away by stress and also lost their focus. A particularly poignant example was a young employee of one of my clients. She came in strong, interviewed well, and showed huge promise. But once she started, she became almost paralyzed by fear of not living up to her potential. This was exacerbated by the high standards of her work group and pressure from her parents as well. She confided to my client that she wasn’t sure she could think any more—her brain had become “fuzzy,” and she wondered, just like my other client, whether she had any value at all. Most likely too many catecholamines going on in her brain.

As a coach, it can be really helpful to know about how the PFC works so you can be aware of what might make a difference for your client. In the first instance, we focused on her values and vision, which helped her find a bigger context for engagement. For the young employee, my client tried some different strategies to help her learn to cope more effectively with stress, and they eventually reached a mutual understanding that the position was not a good fit. It was a classic — and very humane — example of coaching someone out of a job, and the employee left on good terms.

Fun fact to leave you with: “Normal” for women tends to be perfectly in balance, “normal” for men, a bit to the side of too few catecholamines. To me, this explains why often men tend to perform better under the pressure of competition, while for many women, this extra stress makes us less effective. And it’s all a continuum of course.

[1] The Mental sketchpad: why thinking has limits, Amy F.T. Arnsten, Ph.D.